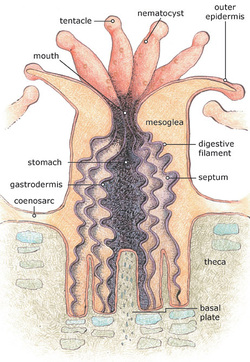

Artwork Credit NOAA/Gini Kennedy Artwork Credit NOAA/Gini Kennedy In a previous post about corals, we discussed the symbiotic relationship between stony corals and their partner algae, Zooxanthellae. Here we’ll talk a little more about individual coral polyps and their anatomy. As we saw in pictures in the last post, coral polyps have tentacles that they can use in hunting, feeding, fighting and even to clean themselves off. These tentacles aren't just arms, they're also weapons: most contain special stinging cells called nematocysts towards the tips. If you've ever been stung by a jellyfish, you've encountered nematocysts before. The entire exterior layer of the coral is covered by the outer epidermis, the coral equivalent of our skin. At the center of the tentacles is a hole, which is the only opening into the gut--so corals use the same hole to take in food and to eliminate wastes (okay, yes, technically they "poop out of their mouths"). When a coral polyp retracts into the skeleton, it does so by expelling all the sea water from inside the gut using muscle contraction. The layer of skin and flesh which extends between each polyp, connecting them, is called the coenosarc. Although polyps are connected by a simple nerve net, we know relatively little about how polyps relate to each other. That said, they certainly can cooperate: one study found that if you selectively fed one polyp in a bleached colony, it would share nutrients to help keep the polyps immediately around it alive. Inside the gut, the gastrodermis (interior layer of skin cells) is a digestive surface which helps break down the things a coral polyp eats. It also has fleshy, digestive "curtains" called mesenterial filaments which drape over calcium carbonate ridges called septa (septum is the plural) to give them more digestive area within the gut. If you make a coral polyp angry, it can extrude (stick out) the mesenterial filaments through the mouth to try to digest or at least hurt whatever is attacking it. Corals can actually go to war with each other using these filaments and other weapons (which we'll talk about in a future post!) The theca is the skeletal "cup" which the coral lives inside, and the basal plate is the bottom of that cup, which the coral is always adding to as part of growth and maintenance (coral calcification and skeletons are also a subject for a future post since they are too awesome and complicated to go into here). Now we have a little more vocabulary for talking about corals, but also a better understanding of how complicated they are--even though many people look at them and see nothing more than a colorful rock. If you can't wait for our next post to get more information on the amazing world of corals, NOAA has a wonderful educational website on corals available at: http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_corals/welcome.html.

1 Comment

Anna

2/24/2021 09:26:05 am

Hi, just wondering if coral feel pain when their outer epidermis is lacerated. Obviously for that to happen, we'd need to know what specifically comprises the outer epidermis and how close nerve fibers are to the surface of the outer epidermis. So my question is; are there any nerve fibers close enough to the surface of the outer epidermis to confidently assume that corals feel pain? Thank you.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Field Notes

Archives

July 2021

Categories |

|

Partner with us! We are always looking for new schools, scientists, and non-profit organizations to partner with. Please contact us here to start a conversation.

Hear from us! Sign up for our newsletter to hear about what is happening at Field School as well as upcoming offers and specials. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed