|

In exciting news, a recent study has published the first ever behavioral and ecological observations of Omura's Whales, expanding scientific knowledge of these rare whales dramatically.

The Omura's Whale (Balaenoptera omurai) was first described in the 1970s based on samples collected by Japanese whaling vessels and a few strandings--but were classified as "pygmy Bryde's Whales" and weren't recognized as a separate species until 2003. Up until now, there were no confirmed field observations of these animals, and very little was known about their behavior and ecology. Recent data collected near Madagascar by scientists from the Wildlife Conservation Society suggests that Omura's Whales are plankton feeding baleen whales, and that they feed and reproduce in the same habitat, unlike many other baleen whales which are known for their long range migrations between feeding and nursery areas. Omura's Whales are related to Bryde's Whales and look similar enough that genetic testing was used to confirm identification of this population, although the authors have gathered data which will make future field observations easier. Based on genetic analysis, the population in Madagascar is believed to be fairly small and isolated. Omura's Whales are considered a "small" tropical whale, with observed specimens all under 40 feet, and studies of diet suggest that they rely on filter feeding for zooplankton (and, from earlier data, small fish and crustaceans). While they are rarely found in tightly knit groups (within several body lengths of each other), when one adult was found, more were often within a few hundred meter range. This longer range association and communication means that studying social groups may be more difficult than with other baleen whales that tend to spend time closer together. It's incredible that there are still animals this size that we know so little about, and these findings are an exciting step in learning more about non-migratory tropical baleen whales. Unfortunately, as the authors point out, this population is threatened by oil and gas development off Northwestern Madagascar. The full paper is available to read for free online here. The ongoing severe California drought is bad news for wildlife, overall. However, in a surprising conservation success, the drought may be helping to fuel the rebound of monarch butterflies along the Pacific coast. As water restrictions increasingly limit how much homeowners are allowed to water landscaping plants, more people are turning to native plants for a drought-tolerant alternative--including milkweed, the species monarchs lay their eggs on. Growing availability of plants that represent critical habitat may help speed a rebound from previous severe population declines.

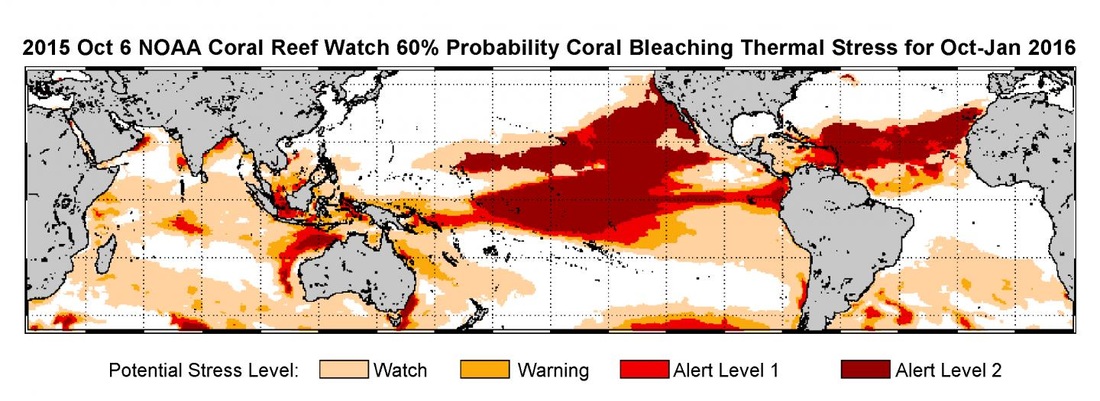

Of course, monarchs are also dependent on a range of other initiatives, from efforts to curb pesticide use to protection of their overwintering grounds in Mexico. If you are interested in helping to create monarch habitat where you live, Monarch Joint Venture has a program to help you find seeds or plants of milkweed native to your area. There are also a lot of opportunities to contribute to monarch research and conservation as a citizen scientist, and they've provided a helpful round-up of those programs here. If you just want to learn more about monarchs and their amazing migrations (up to 3,000 miles!) you can check out some spectacular photos or read more from National Geographic here. In bad news for global corals, NOAA has reported that we are in the midst of a third major global coral bleaching event resulting from temperature stress. Estimates suggest that by the end of 2015, almost 95% of corals in US waters will have been exposed to conditions that can cause them to bleach.

In 2005, the U.S. lost half of our Caribbean coral reefs to a major bleaching event as the result of warming seas. While coral can survive bleaching if the conditions that led to the loss of symbiotic algae (called zooxanthellae) don't last that long, predictions suggest that the current bleaching event will continue into 2016 and so is likely to substantially impact reefs around the world. Corals are one of the marine species we know will be harmed most severely by climate change, as the temperature and chemical composition of the ocean changes. If you'd like to learn more about coral bleaching, there's additional information from NOAA here. You can also read the press release about the current bleaching event here, and if you are a recreational diver, you can help NOAA track bleaching (or the absence of bleaching) by contributing data through the Coral Reef Watch program. |

Field Notes

Archives

July 2021

Categories |

|

Partner with us! We are always looking for new schools, scientists, and non-profit organizations to partner with. Please contact us here to start a conversation.

Hear from us! Sign up for our newsletter to hear about what is happening at Field School as well as upcoming offers and specials. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed